ᐯIᔕTᗩ ᗪIGITᗩᒪ

Remember Remember that Nothing is Forever

Afghan cameleers, imported to Australia camels and all, at a time when by camel was the only safe=ish way for Brits to move themselves and their goods through the many deserts of northern, central, southern and western Australia, left many excellent legacies, including their descendants. One of my very favorites of their influences is the saying often heard in the bars of desert hotels in Western Australia: A man’s not a camel!

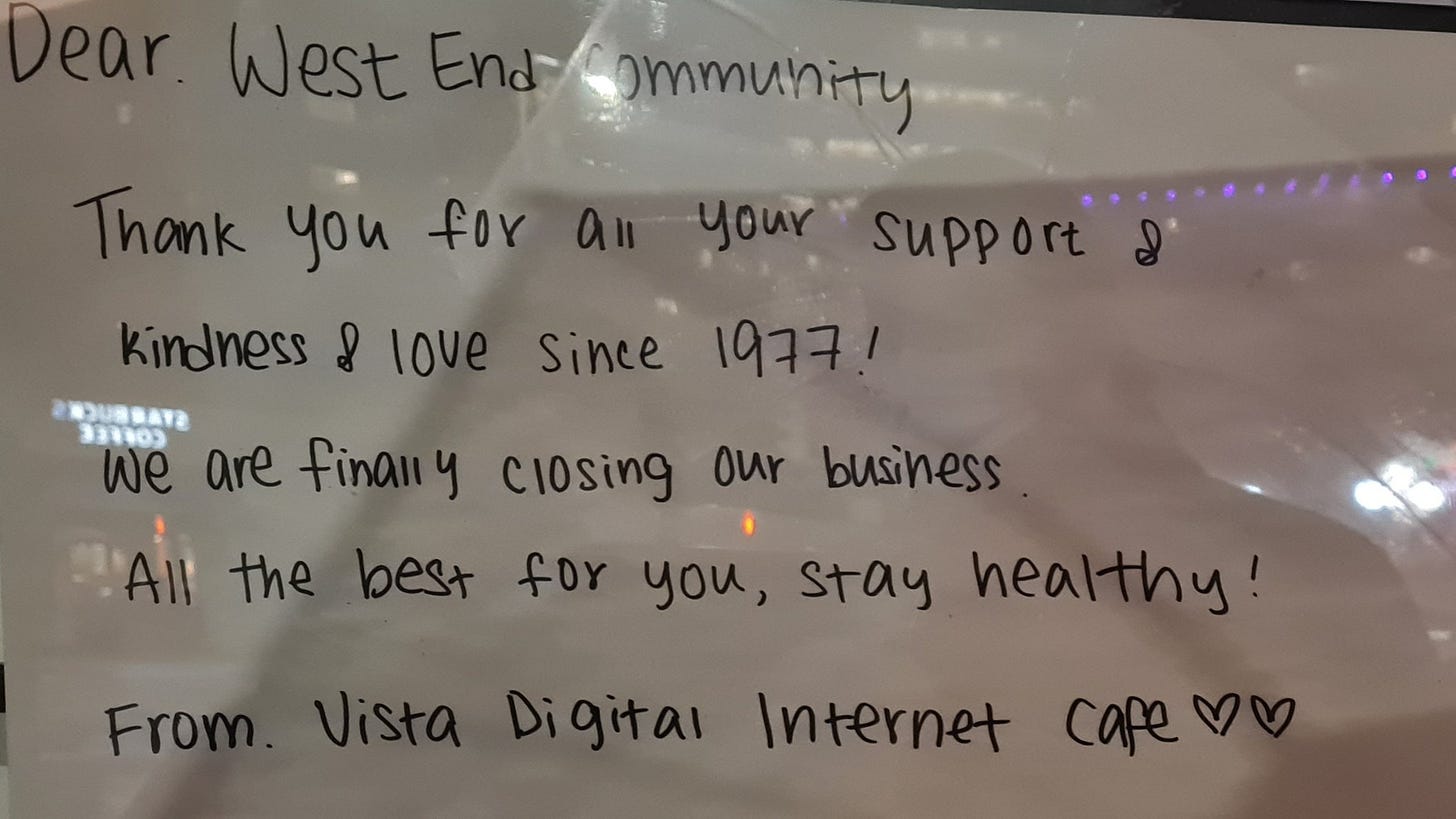

I’m so glad that I happened to be passing it by, in my neighborhood in downtown Vancouver, on the single day on which a closing notice and For Lease sign were up in the window of Internet Coffee, before the space was quickly snapped up by a new tenant.

The last standing internet cafe in these parts wasn’t called Internet Coffee, but we always called it that because the other words on the awning had worn away and couldn’t be read. On the day of its demise, I found out its real name was Vista Digital. It made me think of the child Ray who dies in the novel Mildred Pierce. Her funeral service is the only time she is ever called correctly by her name, Moira, by an Irish priest. Her Californian parents, who’d been given the name, written down, by Mildred’s astrologist, had thought it was pronounced moi-ray like the French moi, with a little accent on the a, and had nicknamed her Ray. It’s a small thing, a nothing, but a nothing among many nothings, which add up to a kind of thoughtlessness.

ᖇEᗰEᗰᗷEᖇ ᖇEᗰEᗰᗷEᖇ TᕼᗩT ᑎOTᕼIᑎG Iᔕ ᖴOᖇEᐯEᖇ

The family of Japanese women who operated Internet Coffee - Vista Digital - offered more than just 20 odd desktop computers with internet access to rent by the minute or hour. They were expert in the services they offered: scanning documents perfectly, even entire books, page by page, graphic design for personalized cards or resumes, almost anything to do with stationary and printing and bookbinding. I once had a relative in San Francisco borrow a book from his library which I couldn’t get in Canada, and post it to me. They scanned the whole novel for me at Vista Digital for a ridiculously low fee, and it was safely returned to the Menlo Park library.

Their shop was very full of machines but very cozy and very dark, for all the screens of course. They displayed cans of drinks and packets of snacks around the shop, which they sold cheaply to the customers who quietly gamed for hours in the glow of a desktop. At Internet coffee I could send a fax, organize a courier, scan a document, buy any kind of envelope, and find out anything I might need to know about international postage, time zones, maps and even tide charts, from the family of women whose shop it was. They seemed to have melded an affinity for paper goods and stationary easily with digital technology. I wish I’d gotten to know them better.

Internet cafes became a natural home away from home for me, much like a good bar, ever since they sprung into more general existence when I was a teen in the 1990s. I transitioned seamlessly from being a library child to being an internet cafe teen, especially since you could still smoke at internet cafes back then. Sometimes I joke that, “Internet cafe is my culture”, but it’s not really a joke. I felt as attached to Vista Digital as I do to my ancestral drinking holes.